In the previous post, we briefly looked into soft and hard attention mechanisms. We discussed why Soft-attention is much more popular than Hard-attention in machine learning. In this post, we look into the details of multi-head attention. We will also study the reasons and effects of using multiple heads in an attention mechanism.

What is Multi-Head Attention?

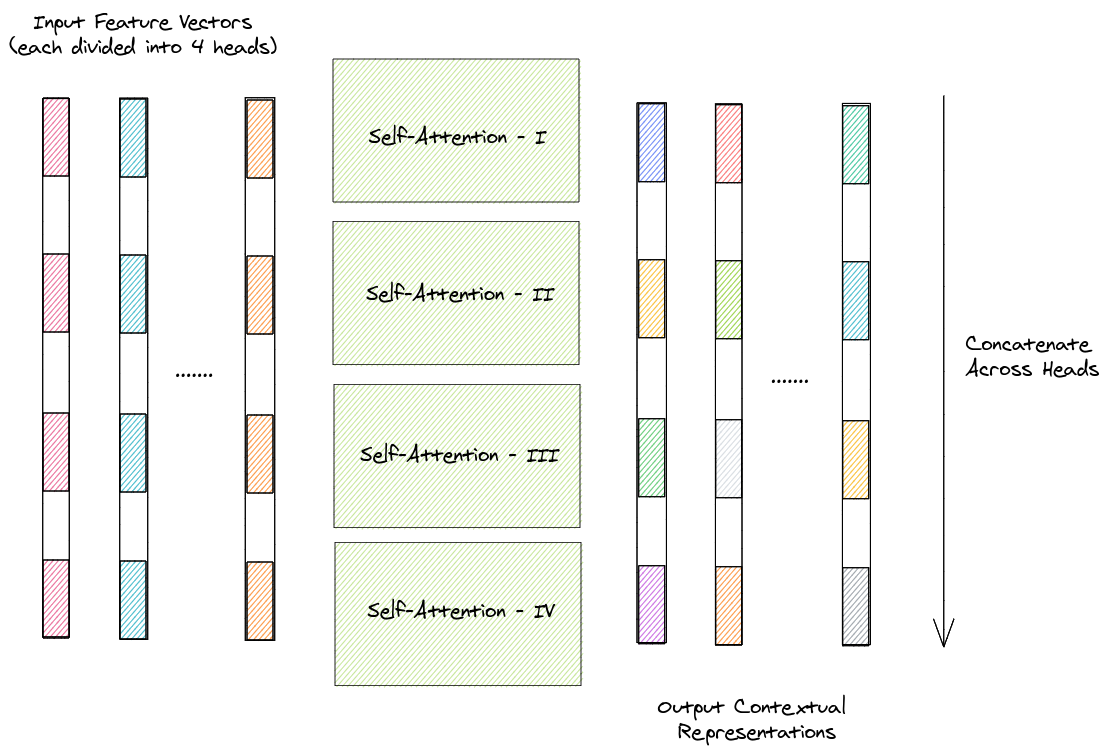

Suppose, the task is to calculate the self-attention over a bunch of vectors. In Multi-Head paradigm, each of these vectors will be divided into a fixed number of chunks called \(heads\). Self-attention is then calculated individually for each set of chunks across the vectors and the outputs of all the chunks are concatenated to give us the contextual representations for each of the vectors.

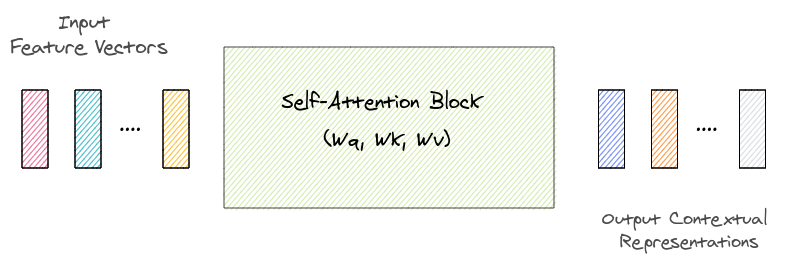

Shown below is a representational figure for the self-attention mechanism that takes in input \(n\) different feature vectores and outputs contextual representation for each of those vectors. The trainable parameters associated with the self-attention mechanisms are the projection matrices \(W_q\), \(W_k\) and \(W_v\) used to project the feature vectors in \(queries\), \(keys\) and \(values\) respectively.

Consider a 4-head attention method. In this case, each of the input feature vectors (say \(512\)-dimensional) is divided into 4 heads (\(512/4 = 128\)-dimensional). Self-attention is then be used to find the contextual representations of each of the four heads across the input vectors. These representations are then be concatenated across heads and passed through a feed-forward layer to output the final contextual representations of each of the input vector. The process is depicted in the diagram below.

In the above scenario, 4 sets of projection matrices \(W_q^{(i)}\), \(W_k^{(i)}\) and \(W_v^{(i)}\) \(\forall i \in \{1,2,3,4\}\) are used to obtain the \(query\), \(key\) and \(value\) triplet corresponding to each head.

Mathematically, for a set of \(n\) \(d\)-dimensional input vectors \(\mathbf{V} = \{v_1, v_2, ..., v_n\}\) and number of attention heads \(h\), we have

\[head\_size = d / h\] \[\mathbf{V}_i = \{v_j[(i-1)*head\_size : i*head\_size] \text{ | } \forall j \in {1..n}\}\] \[head_i = \textbf{SelfAttention}(\mathbf{V}_i; \{W_q^{(i)}, W_k^{(i)}, W_v^{(i)}\}\] \[\textbf{MultiHeadSelfAttention}(\mathbf{V}) = \text{Concat}(head_1, head_2, ..., head_h)W^o\]Where \(\{W_q^{(i)}, W_k^{(i)}, W_v^{(i)}\}\) \(\forall i \in {1...h}\) and \(W^o\) are learnable weight matrices.

While the above diagrams and equations demonstrate the use of multiple heads for self-attention, the same idea can be applied to leverage multiple heads for cross-attention mechanisms also.

Why Multiple Heads?

Multi-Headed attention is a key component of the Transformer, a state-of-the-art architecture for several machine learning tasks. Even though the number of parameters in a multi-head attention mechanism are independent of the number of heads, using multiple heads rather than a single head i.e, the usual attention mechanism improves the performance. Vaswani et al. mention that Multi-Headed attention allows the model to jointly attend to information from different representation subspaces at different positions, which is inhibited by averaging in case of a single head.

Voita et al. evaluate the contribution made by individual attention heads in the Transformer encoder to the overall performance of the model. The authors discover that the different attention heads might serve for different purposes. For the task of machine translation, they characterize attention heads into three types. First, \(positional\) – when the head points to an adjacent token. Second, \(syntactic\) – when the head points to tokens in a specific syntactic relation and third, \(rare\ words\) – when the head points to least frequent tokens in a sentence. They also introduce a pruning method for removing attention heads and observe that the heads which are less interpretable are first to be pruned.

Michel et al. experiment with pruning attention heads at test time. They observe that even if models have been trained using multiple heads, in practice, a large percentage of attention heads can be removed at test time without significantly impacting performance. In case of machine translations, where encoder-decoder architecture of transformer is used, pruning heads causes the performance to drop much more rapidly.

In the next part of this series, we will study graph attention networks in detail.

References

- Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, J., Jones, L., Gomez, L., & Polosukhin, I. (2017). Attention Is All You Need arXiv e-prints, arXiv:1706.03762.

- Elena Voita, David Talbot, Fedor Moiseev, Rico Sennrich, and Ivan Titov. 2019. Analyzing multihead self-attention: Specialized heads do the heavy lifting, the rest can be pruned. arXiv preprint arXiv:1905.09418.

- Michel, Paul, Omer Levy, and Graham Neubig. “Are sixteen heads really better than one?.” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. 2019.

Cited as:

@article{nikhil_attention,

title={Attention! An Other Perspective},

url={https://learningturtle.github.io/Blog/posts/attention_another_perspective_part4/},

journal={Learning Turtle},

author={Nikhil},

year={2020}

}

Postscript

If you find any mistakes/complicacies in our blogs or if you have any suggestions/feedback, do not hesitate to contact us at learningturtle.yt@gmail.com.